Frank C, Kapfhammer S, Werber D, Stark K, Held L (2008): Cattle density and Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli infection in Germany – increased risk for most but not all serogroups

Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 8 (5): 635-643.

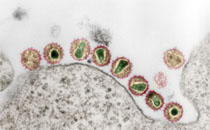

Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) cause severe gastroenteritis and life-threatening hemolytic-uremic syndrome. For STEC of serogroup O157, association between disease incidence and cattle contact has been established in some countries. For other (non-O157) serogroups, however, accounting for approximately 80% of notified STEC gastroenteritis in Germany, the role of cattle in human infection is less clear. For example, an association of non-O157 STEC infection and cattle density has not been investigated. The aim of this study was thus to investigate a potential association between STEC incidence and cattle density in Germany, with special attention to the non-O157 serogroups. We modeled district-level incidence of notified human STEC cases in relation to cattle density, utilizing German notification data from 2001 through 2003. Cattle numbers came from the national "Proof of Origin and Information Database for Animals." A Bayesian Poisson regression model was used, incorporating independent, as well as spatially correlated, district-level random effects into the analysis. We analyzed 3216 German STEC cases. Cattle density was positively associated with overall STEC incidence. The risk for STEC infection increased by 68% per 100 additional cattle/km(2). The magnitude of the risk estimates differed by serogroup and was greatest for O111. A positive association was found for all major disease-causing serogroups (O26, O103, O111, O128, O145, O157) except O91. The association with serogroup O26 (lowest median age of patients) was only borderline significant. Residual variation indicates that additional factors not under study may also be of importance, and that they may be serogroup- and region-specific, too. In conclusion, this study suggests that living in a cattle-raising region appears to imply risk not only for STEC O157, but also for most non-O157 serogroups. Furthermore, the varying magnitude of this risk and the residual variation found for different serogroups indicate that risk profiles for human STEC infection may be serogroup-specific. This needs to be taken into account in risk factor studies for non-O157 STEC, ideally by reporting risks separately by serogroup.